One of the first things the League of Women Voters went to work on was independent citizenship for married women. It was to undo the 1907 Expatriation Act[1] by which a US born woman was stripped of her US citizenship, adopting her husband’s upon marrying a foreign man who was not naturalized.

Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled…

Sec. 2 – That any American citizen shall be deemed to have expatriated himself when he has been naturalized in any foreign state in conformity with its laws, or when he has taken an oath of allegiance to any foreign state.

Sec. 3 – That any American woman who marries a foreigner shall take the nationality of her husband. At the termination of the marital relation she may resume her American citizenship, if abroad, by registering as an American citizen within one year with a consul of the United States, or by returning to reside in the United States, or, if residing in the United States at the termination of the marital relation, by continuing to reside therein…

Approved March 2, 1907[2]

It was confusing enough that foreign men could vote in Indiana…

if they had filed their “first papers”, meaning if they had declared their intention to become naturalized, and if they had lived

- in the country for a year,

- in Indiana for 6 months,

- 60 days in the township

- and 30 days in the precinct.

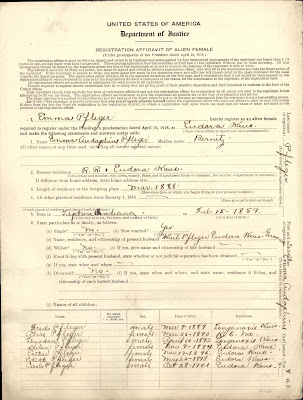

Adding insult to injury, many of these men, who for one reason or another had failed to finish the naturalization process, were required to register as ‘enemy aliens’ in February 1918. Their wives would have to follow suit in June 1918. Few of these registrations still exist. I have found none in Miami County so far. I was able to find an example online at FamilySearch.org[3], and also at the National Archives page[4].

Men registered in February 1918 in Miami County. The process was likely the same for the women. They registered in June and the newspapers give details about their experience.

The women had 10 days during which to comply. They were asked to bring 4 current photographs of themselves, and were required to fill out a 4 pages-long form in triplicate.

The questions asked

- about their birth

- when they emigrated,

- what ship they sailed on

- when and where they landed in America

- where all she had lived in the US

Each questionnaire included a page for finger-prints, along with the photograph.

Here is one of a Tipton, IN woman living in Kansas, married to a German.

It gives a good idea of how much work and how much time it took to go thru the process.

One filled questionnaire was sent to the federal government, another went to the state and the third remained on file at the local police station.

An identification card was then issued to each registrant, on which to paste the 4th photograph.

Registered ‘enemy aliens’ were not

allowed to change addresses or move within the city without first getting a permit from the police

station and this all had to be reported to the state and to Washington DC. No need

to say many suffered great embarrassment and were rather angry. Many of these families had sons

serving in the military or otherwise and yet they had to comply or risk imprisonment. It did however hasten the pace for some to finish their naturalization process once the war was over.

In Miami County, the newspapers reported that 82 men[5] and 69 women[6] registered.

At least 18[7] of these women were born in the US and 2 in the Allied nation of France:

- Marie Ahnert, daughter of Henry Diller and Pearl Hinkle, born in Miami County, IN

- Margaret Baltzli, daughter of Michael Sand and Eva Heinrich, born in France

- Pauline Dallmon, daughter of Jacob Ginter and Frances, born in MN

- Sophia Ehlers, daughter of Friedrich Hockelberg and Anna Johanna Scholtz, born in Woodville, IN

- Theodora Henrietta Kemps, daughter of Gustave C Kemps and Charlotte Kurz, born in Peru, IN

- Sophia Krathwohl, daughter of Fred Hager and Hannah Stark, born in France

- Susanna Kuch, daughter of Samuel Troyer and Sarah Schrock, born in Salt Creek, OH

- Catherine Lentz, daughter of Frank Eisbrenner and Anna Hannig, born in Peru, IN

- Bertha Leithold, daughter of Herman Kemps and Henrietta Lang, born in Rochester, IN

- Anna Lutz, daughter of Fred C Bulk and Dorothy Pohlman, born in IN

- Anna B Pritz, daughter of Christopher Ploss and Anna Martha Stemler, born in Logansport, IN

- Martha Richter, daughter of August Menzel and Amelia Bottel, born in Peru, IN

- Helen Rudolph, daughter of Charles Lewis Ahnert and Marie Voit, born in Peru, IN

- Clara Schantz, daughter of Frank Groeschel and Marie T. Feitz, born in Fort Wayne, IN

- Augusta Schmidt, daughter of William Butzin and Sabina Eisbrenner, born in Peru, IN

- Emma Schmidt, daughter of Ferdinand Schmidt and Anna Wendt, born in Peru, IN

- Ernestine Strominger, daughter of Henry Conradt and Marguerite Finster, born in Peru, IN

- Maud Weinke, daughter of Dewitt Latham and Rachel E. Taylor, born in Peru, IN

- Ida Welke, daughter of Fred Bulch/Bulk and Dora Pohlman, born in Kokomo, IN

- Emma Zipperian, daughter of Leonard Kolb and Maria Barbara Waltz, born in Peru, IN

Most professions were not hindered by the Expatriation Act of 1907. Such was not the case for women who practiced law or whose job required them to be US citizens. This law also made affected women, vulnerable to detention and deportation[8].

On the other side of the Expatriation Act coin, foreign born

women who gained US citizenship by marriage were able to retain it, even if

they divorced. They could 'return' that

citizenship by making a formal renunciation before a court.

Before the 19th Amendment passed, it was probably of little consequence to the registered "enemy alien women" of Miami County, who were housewives. None appear to have been affiliated with the Woman’s Franchise League but they may have belonged to a union of the WCTU (none in leadership positions that I found) or another Woman’s Club of the day where voting rights were discussed.

In 1918, the Woman's Franchise League was continuing its work of recruiting although it had been combined with the additional responsibility of War Work.

In Miami County, 8,503 women, 16y and up, registered with the Women's Section of the Council of Defense, whose goal was to make an inventory of what "Woman Power" looked like within its 'borders'. Many of these enemy-alien women knitted socks for the soldiers and saved fuel and food with as much patriotism as their neighbors, so I am not suggesting they were isolated by any means, or not exposed to the enthusiasm at the idea of having a voice in the affairs of government.

To correct the injustice done to American-born women, the League of Women Voters supported[9] the Curtis-Rogers Woman

Citizenship Bill, promoting “Independent Citizenship for Married Women”[10], principle already

adopted by the League at its first convention in February 1920 and presented to the parties as planks for the 1920 Presidential Elections.

|

| Marie Stuart Edwards presenting the planks to Senator Harding during Social Justice Day Event in October 1920 |

I checked the naturalization status of these families on the 1920 census and it contradicted in part what the registrations had laid out. But since I found no naturalization records available for these families, whether or not these women voted in the first presidential election after the ratification of the 19th Amendment will remain a mystery. For the time being. That's the beauty of a blog article. You can always update it!

| ||

| https://iiif.lib.harvard.edu/manifests/view/drs:462301307$20i | |

The bill treated women as individuals, separate from their spouses, and required all to follow naturalization process either to gain or regain US citizenship. It is still strange to think a US born woman, having lost her citizenship by marriage, should be required to re-establish herself as a US citizen but that’s how it worked out.

And the Bill, once passed, remedied the professional dilemma of some adversely affected.

Of course, immigration and naturalization laws changed again but not in the way of automatically granting citizenship by marriage.

Thumbing thru Maud Wood Park’s papers, at the Schlesinger Library, Harvard University, I came across her account of the League’s work to better society. The 1920-1921 Legislative report[11] follows the different points of the planks. They sure moved a lot of ‘earth’ in a short time: concerns over children’s education, health and overall well being, at school and elsewhere.

The summary notes their work[12] towards

o Universal Physical Training for both sexes from ages 6 to 18

o More adequate provision for vocational training in Home Economics

o Providing a Library Information Service in the Bureau of Education

o Sheppard-Towner Bill for Maternity and Infant protection - PASSED

o Establishment of the Women’s Bureau: still working on “Equal pay for Equal work”

o Establishment of Federal and State Employment Service with Women’s Department

o Minimum wage Bill, Johnson-Nolan Bill: $3/day for Federal employees – Defeated

o Retirement system for Public employees

o Public Appropriations for the Dissemination of Education in the Laws of Physical, mental and racial health. – Program outline in the League’s flyer[13] by Dr. Valeria H Parker.

o American Citizenship[14]: Independent Citizenship for Married Women: the Cable Bill would be the big focus of 1922 – PASSED

Interestingly enough the League of Women Voters did not support the Equal Rights Amendment.

As early as March 1923, when Congress passed an Act that recognized “the principle of equal compensation for equal work irrespective of sex”, the League felt caution should be observed in pushing what Maud Wood Park refers to as the “so-called Equal Rights Amendment”[15]. It seemed to be more about not rocking the foundation of family relationships.

In 1945, the Indianapolis Star quoted then President of the League, Mrs. John K Goodwin: “Passage of the Equal Rights Amendment does not necessarily mean equal pay for equal work as the proponents of the legislation claim. Women will lose rather than gain by passage of equal rights because the amendment throws into jeopardy the entire protective laws which take into consideration the biological difference of men and women.”

Let's tackle that some other time!

Here is the League's 1922 Legislative Calendar[16] and 1923

[3] https://www.familysearch.org/search/collection/1878523 for California

[4] https://catalog.archives.gov/id/602456, https://catalog.archives.gov/id/286181 for Kansas; https://catalog.archives.gov/id/5917191 for Nebraska

[5] The Sentinel 16 Feb 1918, Peru, IN

[6] The Peru Journal 28 Jun 1918, Peru, IN; The Sentinel 29 Jun 1918, Peru, IN

[7] The list includes 8 women whose parents/birth place could not be identified.

[8] https://immigrationhistory.org/item/an-act-in-reference-to-the-expatriation-of-citizens-and-their-protection-abroad/

[10] “Independent Citizenship For Married Women,” Social Welfare History Image Portal, accessed March 16, 2021, https://images.socialwelfare.library.vcu.edu/items/show/92.

[11] Harvard University, Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America / sch01035c00263

https://iiif.lib.harvard.edu/manifests/view/drs:464452487$143i

[12] Republican Northwestern, 13 Feb 1920

No comments:

Post a Comment